Conventional ultrasound (cUS) and functional ultrasound (fUS) may both use megahertz-level sound waves to image inside the body, but beyond that, the similarities end. In this perspective article, we aim to clarify the differences between the two techniques, by taking a look at the underlying technology. We’ll then talk about the unique advantages of fUS compared to cUS, and finish with a discussion of why that makes it an ideal choice for functional imaging of blood flows in the brain.

Understanding ultrasound

Since it was first introduced as a clinical technique in the 1940s, ultrasound has established a firm place in the arsenal of imaging techniques used diagnostically by clinicians and researchers, thanks to its ability to probe the inner structures of the body non-invasively.

Although the principle of ultrasound is simple (see video below), both the number and complexity of ultrasound modalities have increased substantially, with options such as B-mode, M-mode, pulsed-wave Doppler, color Doppler and power Doppler familiar to many in the field.

This complexity can make it difficult to appreciate the advantages offered by a particular modality, or the applications to which it is best suited. A case in point is the relatively new technique of functional ultrasound (fUS), which is used in Iconeus One and a couple of other systems on the market. In particular, it’s not always easy to appreciate what differentiates it from conventional ultrasound (cUS), which is used in the vast majority of ultrasound scanners.

So in this article we’ll explain how cUS and fUS work (in as non-technical a way as possible!), and why only fUS provides the combination of sensitivity, temporal resolution, spatial resolution and field of view that make it ideally suited for imaging blood flows in the brain.

The essentials of conventional ultrasound

Conventional ultrasound scanners most commonly use a series of 128 (or 256) point-source transducers arrayed over a length of about 5 cm. Each one emits an ultrasound pulse, with a slight delay between them so that the waves all reach the desired region at the same time. This maximizes the strength of the echo from that focal region, providing a strong signal. If there are scatterers in the tissue, then the echoes from them will bounce back to the transducers. The signals from all the transducers are then processed to create a 1D image ‘line’.

Typically, this process will be repeated 128 (or 256) times, with a different time delay applied in each case, so that the ultrasound is successively focused from left to right. Usually, the whole series of acquisitions is carried out at four focal depths in order to ensure a well-resolved 2D image ‘slice’ across the whole region of interest.

The unavoidable trade-off with conventional ultrasound

This is all very well, but sending and receiving all these separate signals takes time. For example, one transmit/receive pulse from a single transducer will take 30 µs to reach a depth of 5 cm and another 30 µs to return. So if you have 128 transducers and you’re combining data from four focal depths, then that means that it takes 30 µs × 2 × 128 × 4 = 32 ms to acquire a single 2D ‘slice’.

This places a limit on the rate of acquisition of 2D frames (the so-called ‘frame rate’). From the above calculations, this would be 1/0.032 = 31 frames/s, or more generally in the range 25–50 frames/s. This is fine if you’re imaging tissues that are moving slowly, but for tissues that are moving much faster than a beating heart (to pick a relevant example), then you’re fundamentally limited by this frame rate.

One solution is to only collect data from a contiguous subset of the transducers, reducing the time taken to obtain a ‘complete’ image. So for example, if you want to achieve 250–500 frames/s at a depth of 5 cm, then you would only collect data from one-tenth of your transducers, reducing the width of your image from 5 cm to 5 mm. Or to go to the extreme, to obtain a frame rate of about 5000 frames/s, then you would have to collect data from one transducer, reducing the width of your image to just 0.5 mm (in what’s known as ‘pulsed-wave Doppler’).

Alternatively, you could continue to use the data from all your transducers, but instead limit the focal depth, allowing you to pack more transmit/receive pulses into a given time. Either way, with conventional ultrasound there is an unavoidable compromise between temporal resolution and field of view.

The role of plane waves – and the link to ultrafast ultrasound

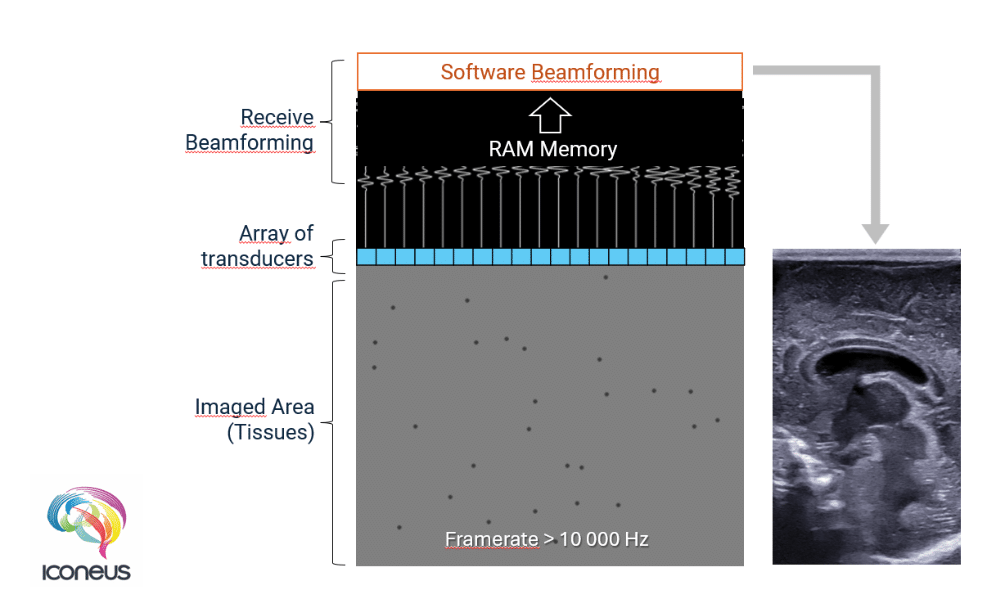

So, how can this trade-off be overcome? The solution, proposed in the late 1990s and developed in the succeeding years by a team involving Iconeus founder Mickael Tanter,1 is to fire all the transducers at once. That creates a ‘plane wave’, eliminating the time delay inherent in the transmit/receive pulse sequence, and making possible what is termed ‘ultrafast ultrasound’.

Plane waves, being unfocused, cause all scatterers to produce echoes at more-or-less the same time. You might think that this combined signal would be more difficult to process, and you’d be right – in fact, storing and processing this data in real time only became practical for 128-transducer arrays from about 2016 onwards, with the advent of more powerful computer chips. Nevertheless, although this data is complex, with the aid of modern parallel processing techniques (which we use in the software for Iconeus One), it can be rapidly deconvolved to yield information on the position of all the scatterers.

But what’s more important is that using plane-wave transmission dramatically cuts down the time needed for imaging. So it typically takes just 0.1–0.5 ms to acquire a single 2D ‘slice’, which means that the frame rate of fUS is an impressive 10,000 frames/s – a value that is 200 times higher than cUS.

Combining ultrafast ultrasound and signal processing to achieve fUS

And this is where functional ultrasound (fUS) comes in. By using the ultrafast ultrasound technique to transmit signals and receive echoes, with fUS it is possible to achieve high temporal resolution and high spatial resolution, across a region that is sufficiently large to be diagnostically useful.

This of course is great, but a side-effect of the unfocused nature of the plane-wave ultrasound is that there is an increase in image noise (‘speckle’), and a resultant drop in sensitivity. The solution to this, described in a 2011 paper2 and implemented on Iconeus One, is to run each acquisition using a series of plane waves each at slightly different angles, and then sum them. This so-called ‘coherent plane-wave compounding’ has the effect of cancelling out a substantial proportion of the background noise for a relatively modest decrease in the frame rate (to be specific, compounding N plane waves decreases the frame rate by a factor of N). The good thing about this approach is that the number of compounded scans can be adjusted entirely in the software, meaning that it is easily fine-tuned to the needs of the application.

This increase in the signal-to-noise ratio naturally leads to higher sensitivity – a benefit that is enhanced further by the ability to carry out better signal processing. That in turn is due to the fact that all parts of the tissue are sampled simultaneously, rather than at separate points in time, making pixel-to-pixel comparisons more robust. The overall result is that fUS is approximately 100 times more sensitive than cUS, enabling it to detect much smaller movements.

Why ‘ultra-high-frequency’ transducers cannot perform fUS

Through all of this discussion about image quality in functional ultrasound, we’ve not touched on one aspect – the specifications of the transducer. This might seem counter-intuitive, because in principle, increasing the frequency of the ultrasound waves should improve resolution by allowing smaller features to produce echoes. But in practice, higher frequencies are more effectively absorbed by tissues, resulting in poorer transmission and restricted imaging depth.

For most preclinical applications – whether cUS or fUS – a good compromise between imaging depth and spatial resolution is achieved with a transducer ultrasound frequency of 15 MHz, and so this is what we use for most of our transducers. (Just to be clear, although transducers used for cUS could in principle be used in our own Iconeus One system, because they’re so fundamental to overall performance and reliability, we’ve set up the system to only accept our own transducers).

But what about the ‘ultra-high-frequency’ transducers marketed for use with conventional ultrasound and optoacoustics? Some of these are rated up to 70 MHz, and although these provide improved spatial resolution compared to conventional transducers used for cUS, because of signal drop-off, they’re limited to resolving features within the first few millimetres of the surface. And of course, they also suffer from the awkward compromise between temporal resolution and field of view that affects all cUS systems. So even though ultra-high-frequency transducers are useful for certain niche applications, they cannot achieve the wide-range functional imaging that is offered by fUS.

Why is fUS primarily used for brain imaging?

The applications of cUS are of course well-known, with pregnancy monitoring perhaps being the most familiar to the wider public, but with many other uses, including routine investigations of the heart, eyes and breast.

In principle, fUS can also be used to image all these tissue types, and indeed, the technique of ultrafast ultrasound that underpins fUS was originally developed with tumor imaging in mind. But the more advanced hardware and software that’s needed for fUS means that it makes most sense to use it for the applications that cannot be adequately done with cUS.

And what cUS tends to struggle with most is the imaging of blood flows, especially low flows (less than 2 cm/s). This is because the relatively low frame rate of cUS means that the only option for separating motions with different frequencies is to use a simple ‘high-pass’ filter. The problem here is not the filters themselves (they can actually work fine with fUS data), but the combination of the filter and the low frame rate. This makes it impossible to get rid of the unwanted signals from the slow motion of tissues at the same time as keeping all the information on slowly-moving blood cells. Even when imaging arteries (in which blood can flow at rates approaching 1 m/s), the switch to low flows during the diastolic phase usually means that this phase is not well-imaged.

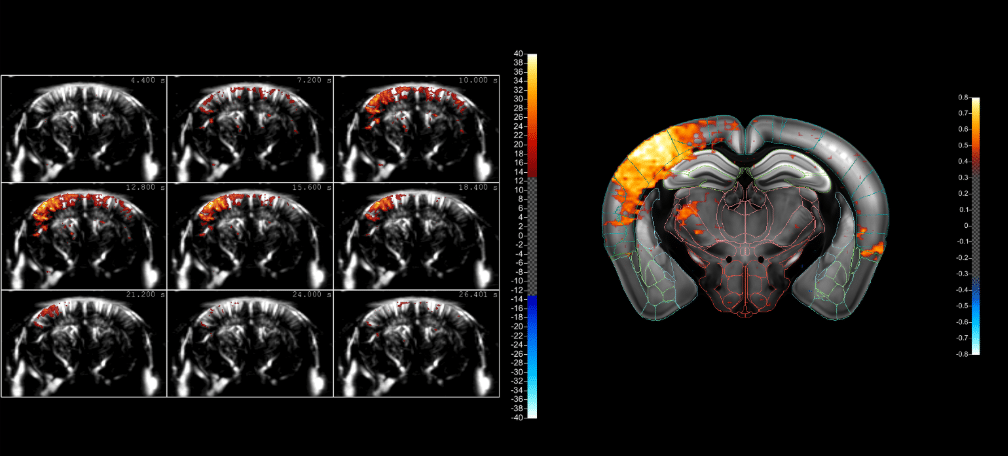

In contrast, the complete spatial and temporal coverage of ultrafast ultrasound used for fUS means that there’s a better way to separate fast movements and slow movements – a mathematical approach called singular value decomposition (SVD). Without getting into the details , SVD filtering works by separating highly coherent, large-scale motions (e.g., tissue motion from arterial pulsations) from the more complex, decorrelated fluctuations generated by blood flow. This allows slow movements to be filtered out easily, leaving a clear image of the relevant hemodynamic changes. The lower detection limit on blood flow remains the same for fUS as for cUS (1 mm/s), but now this is across the whole brain, not just a single-point measurement.

Such low flows are typical of the smallest blood vessels, and amongst these, the arterioles within the brain are of particular interest. This is because the blood flows in such vessels increase when neurons are activated – a tightly-regulated link known as the ‘neurovascular coupling’.

So by monitoring the blood flows in these vessels using fUS, we can infer the activation of certain brain regions. This allows us to see the effect of sensory stimulation, or probe the functional connectivity between brain regions, and even gain insights into disease mechanisms. And what’s more, using Iconeus One, this can be done in real time!

Ultrasound techniques compared

For ease of reference, below is an at-a-glance comparison of cUS and ultrafast US (the technology that underpins fUS).

Towards the future of fUS

The unique capabilities of fUS, coupled with the intense research interest in brain science, means that it’s becoming a valuable tool for brain researchers.3 And as fUS matures, it’s increasingly appealing to sectors outside traditional academic research. For example, there have already been fruitful collaborations with the pharma industry to investigate fUS as an alternative to conventional fMRI methods. Similarly, research hospitals and clinics have been looking at the potential of translating preclinical fUS methods on rodents and other mammals into ones that will work in humans.

In this way, fUS is firmly positioned at the forefront of brain imaging used for scientific discovery – a field where it offers the greatest advantage over cUS, where the focus is on routine diagnostics. As we’ve seen, these advantages hinge on the way in which the ultrasound transducers are fired, and the careful balancing of trade-offs in performance. All that is courtesy of decades of intense effort into optimizing the fUS technique, led by experts at the interface of physics, signal processing and neuroscience.

And, we’re happy to say, many of those experts are to be found here at Iconeus.

References

1. L. Sandrin, S. Catheline, M. Tanter, X. Hennequin and M. Fink, Time-resolved pulsed elastography with ultrafast ultrasonic imaging, Ultrasonic Imaging, 1999, 21: 259–272, https://doi.org/10.1177/016173469902100402.

2. E. Macé, G. Montaldo, I. Cohen, M. Baulac, M. Fink and M. Tanter, Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain, Nature Methods, 2011, 8: 662–664, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1641.

3. T. Deffieux, C. Demene, M. Pernot and M. Tanter, Functional ultrasound neuroimaging: A review of the preclinical and clinical state of the art, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2018, 50: 128–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.001.